Quenching Defects in Forgings: Cause, Prevention & Solution

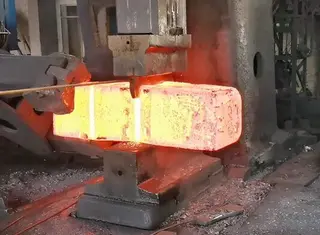

In industrial production, the quenching of forgings is a crucial process. Through quenching, the strength, hardness, and wear resistance of forgings can be significantly enhanced, thereby meeting the performance requirements of various mechanical components in practical applications. However, the quenching process is often accompanied by some undesirable defects, which not only affect the appearance quality of forgings but may also seriously impact their service performance. Therefore, thoroughly investigating the types and causes of quenching defects in forgings and finding effective solutions is extremely important for improving product quality and reducing production costs.

Quenching Distortion: The Dual Challenge of Volume and Shape

Quenching distortion mainly manifests as volume distortion and shape distortion. Although these two types of distortion differ in form, both negatively affect the quality of forgings. Understanding their causes and characteristics is key to preventing and addressing distortion problems.

1. Volume Distortion

The changes in the internal structure of a forging before and after quenching are the key factors leading to volume distortion. Different microstructures have different specific volumes. From martensite to bainite, and then to pearlite and austenite, the specific volume decreases sequentially. When a forging with a pearlitic original structure transforms into martensite after quenching, its volume will expand; conversely, if there is a large amount of retained austenite in the forging, the volume may shrink. This volume change is particularly important for forgings requiring high precision, as it directly affects the dimensional accuracy of the workpiece.

2. Shape Distortion

Shape distortion refers to changes in the relative positions or dimensions of various parts of a forging, such as bending of plates and rods, expansion or contraction of internal holes, and variation in hole spacing. The formation of such distortion has multiple causes, mainly including:

- Uneven Heating Temperature: When there are temperature differences in different parts of a forging during heating, thermal stress is generated, causing distortion. Additionally, improper placement of the forging in the furnace can cause creep distortion due to self-weight at high temperatures.

- Effects of Residual Stress: During heating, as the temperature rises, the yield strength of steel decreases. If residual stresses already exist in the forging, such as cold working stress, welding stress, or machining stress, when these stresses exceed the high-temperature yield strength, uneven plastic deformation occurs, leading to shape distortion and relaxation of residual stress.

- Non-uniform Cooling During Quenching: During quenching, different parts of the forging cool at different rates, creating thermal stress and structural stress, which lead to localized plastic deformation. Complex-shaped forgings, due to their structural characteristics, are more prone to distortion because heating and cooling rates are inconsistent.

Strategies to Prevent Distortion

The impact of quenching distortion on product quality is evident, so preventing distortion is a crucial step in production. Optimizing heat treatment processes and part design can effectively reduce the likelihood of forging distortion, improving product qualification rates and performance.

1. Reasonable Heat Treatment Process

Adopting a reasonable heat treatment process is key to reducing forging distortion. Specific measures include:

- Lowering Quenching Heating Temperature: Properly reducing the heating temperature can decrease thermal stress and structural stress, thereby lowering the likelihood of distortion.

- Slow Heating or Preheating: For forgings with complex shapes or large cross-sections, slow heating or preheating ensures a more uniform temperature distribution, reducing thermal stress during heating.

- Static Heating Method: For extremely long and thin forgings, to avoid impact from salt bath magnetic agitation, the static heating method with power-off heating can be used.

- Rapid Heating: For small cross-section forgings with low core strength requirements, rapid heating shortens heating time and reduces thermal stress accumulation.

- Proper Binding and Suspension of Forgings: During quenching, proper binding and suspension maintain stability during heating and cooling, reducing distortion caused by factors such as self-weight.

- Reasonable Quenching Method: Based on the shape and structural characteristics of the forging, selecting appropriate quenching methods, such as staged quenching or isothermal quenching, can effectively control cooling rates, reducing thermal stress and structural stress.

- Manual Reverse Deformation: Based on the shape characteristics and deformation patterns of the forging, manually pre-deforming the forging before quenching to counteract expected post-quenching distortion can reduce overall distortion.

2. Reasonable Part Design

Rational part design also plays an important role in reducing forging distortion. Key considerations include:

- Symmetrical Shape: Strive for symmetrical shapes and avoid large differences in cross-section to reduce distortion caused by uneven cooling.

- Closed Structures: For slot-shaped or open forgings prone to distortion, make them into closed structures before quenching, e.g., add ribs at slots and cut them after quenching, to reduce the possibility of slot expansion or contraction.

- Process Holes Layout: On some complex forgings, adding process holes can reduce cavity shrinkage.

- Composite Structures: For complex forgings, use composite structures by dividing a complex forging into simpler parts, quenching them individually with minor distortion, and then assembling them to reduce overall distortion.

- Correct Steel Selection: For high-precision tools requiring minimal quenching distortion, choose low-distortion steels; for high-precision plastic molds, pre-hardened steels can be used, providing better dimensional stability during quenching, suitable for various forgings.

3. Importance of Forging and Pre-Heat Treatment

Forging and pre-heat treatment are also crucial for reducing quenching distortion. Severe carbide segregation and banded structures can make forging distortion anisotropic or irregular. Reasonable forging processes improve carbide distribution, reducing distortion and enhancing service life. Proper pre-heat treatment, such as spheroidizing annealing, improves the original microstructure of the forging and reduces deformation tendencies during heat treatment.

Distortion Correction Methods

- Cold Press Straightening: Apply external force at the highest protruding point of a bent forging to induce plastic deformation; suitable for shaft-type forgings below 35 HRC.

- Hotspot Straightening: Heat protruding areas with an oxy-acetylene flame, then rapidly quench with water or oil; suitable for forgings with hardness above 35–40 HRC.

- Straightening While Hot: When the forging cools to near Ms temperature after quenching, use the excellent ductility and phase transformation superplasticity of austenite to correct distortion.

- Tempering Straightening: Apply external force and then temper the forging at temperatures above 300°C, correcting distortion through thermal stress during tempering.

- Counter-Striking Straightening: Continuously strike concave areas with a steel hammer to induce localized plastic deformation and achieve correction.

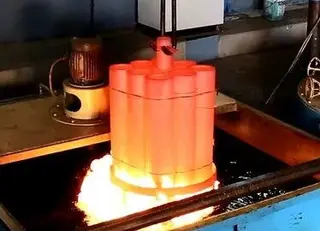

- Hole Shrinkage Treatment: For holes that have expanded after quenching, heat to 600–700°C until red-hot, cover both ends with thin plates to prevent water ingress, then rapidly quench in water to use thermal stress to shrink the holes.

Quenching Cracks

Quenching cracks are a serious issue during heat treatment, caused when quenching stress exceeds the material’s fracture strength. Cracks are usually distributed intermittently in series. The fracture surface shows traces of quenching oil or salt water, without oxidation, and no decarburization is present on either side of the crack.

1. Mismatch Between Material and Process

- Disorganized Material Management: Mistakenly using high-carbon steel or high-carbon alloy steel as low- or medium-carbon steel and water quenching causes excessive stress and easy cracking.

- Inappropriate Quenching Medium: Water-oil dual media or excessive water content can lead to cracks.

- Dangerous Dimensions of Incompletely Hardened Forgings: Cracks easily form at the junction where core hardness is 36–45 HRC.

- Most Dangerous Quenching Dimensions: Forgings with diameters 8–15 mm for water quenching and 25–40 mm for oil quenching are most prone to cracks.

2. Surface and Internal Hazards

- Surface Decarburization: Severely decarburized forging surfaces are prone to network cracks.

- Speciality of Deep-Hole Forgings: Deep-hole forgings with small inner diameters are prone to longitudinal cracks.

3. Improper Heating and Cooling

- Excessive Heating Temperature: Large-section, high-alloy forgings are prone to grain coarsening, high martensite content, and quenching cracks.

- Repeated Quenching Risks: If stress from the previous quenching is not relieved, repeated heating easily causes cracks.

- Poor Original Microstructure: Forgings of high-carbon steel with substandard spheroidizing annealing are prone to cracking.

- Material Defects: Non-metallic inclusions or carbide segregation along the rolling direction form banded distribution, reducing transverse performance and causing cracks.

4. Measures to Prevent Quenching Cracks

Optimize section design to avoid stress concentration.

Select high-hardenability alloy steel for forgings.

Control raw material quality to avoid microcracks, inclusions, and carbide segregation.

Pre-heat treatment to avoid normalizing or annealing defects.

Select heating parameters to prevent grain coarsening.

Choose quenching medium and method appropriately, locally wrapping sharp corners, thin walls, and holes.

Temper in time to relieve residual stress.

Insufficient Hardness

If the surface hardness of a forging after quenching is lower than the hardness value of the steel used, it will severely affect wear resistance and service life. Causes include:

- Insufficient heating during quenching: Austenite not fully transformed to martensite.

- Cooling speed too slow: Incomplete austenite transformation.

- Surface decarburization: Reduces carbon content on the forging surface.

- Raw material issues: Chemical composition or inclusions do not meet standards.

- Quenching process issues: Improper workpiece placement or delayed tempering.

Prevention Measures

Properly control heating temperature to ensure complete austenite transformation.

Select suitable cooling medium and control forging cooling rate.

Prevent surface decarburization by using protective atmosphere or coating.

Strictly control raw material quality.

Optimize quenching process to ensure uniform cooling and timely tempering.

Conclusion

The quenching process of forgings is a complex and delicate process. Although it can significantly improve forging performance, it is prone to various defects, such as quenching distortion, cracking, and insufficient hardness. These defects not only affect product appearance but may also seriously impact the service performance of forgings. Therefore, thoroughly understanding the types and causes of quenching defects in forgings and taking effective preventive and corrective measures is extremely important for improving product quality and reducing production costs. Through reasonable heat treatment processes, part design, forging and pre-heat treatment, and strict control of the quenching process, quenching defects can be effectively minimized. At the same time, for defects that have already occurred, using appropriate correction methods can partially recover losses. Only by continuously optimizing the quenching process and improving forging production technology can one remain competitive in the market and provide high-quality forgings for industrial production.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Quenching Process by Remaining Heat from Forging

- Jun 16, 2015

Why Quenching and Tempering for Steel Forgings?

- May 30, 2024

Essential Quenching Techniques for Forged Components

- Oct 17, 2024

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

Quenching technology of straight seam welded pipe

- Jul 07, 2023

Quenching Process Analysis of Low-Carbon Steel Pipes

- May 28, 2025

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Supplier Website

Source: http://www.forging-casting-stamping.com/quenching-defects-in-forgings-cause-prevention-solution.html